|

Dr Beth Todd Bazemore

February, 1999

Q: Tell me about your background.

Well, I was born in 1958 in near Buffalo New York near the Seneca reservation and a

that time there was a project called the Indian adoption project. It was run by the um,

child welfare relief. And the idea was um, this was during 58, 59 and the early 60’s

to um…people from the child welfare league swept through the reservations of New York

state and remove children, infants and young children who were felt to be, not taken care

of Properly. The problem of the definition of not being taken care of properly meant that

if a mother was young, if a child was being cared for by grandparents, things like that,

um there was no recognition that that was the traditional way that Indian children, many

times their grandparents or grandmothers were their primary care takers, and they removed,

I think it was three hundred forty kids total during those years. I was one of those

children. The idea was that if those young children were adopted into white homes, that

they would stand a better chance at growing up. That they would …that growing up on a

reservation um in poverty and all those things, they thought was going to be detrimental

to the children and so their best chance would be to be raised in a white family and

assimilated into white society. It was during a time when there were many policies of

assimilation going on across the country, boarding schools, relocation programs, things

like that. The general philosophy at that time was that assimilation was the best thing

for Indian people.

Q: What led to that?

I think there’s never really been an understanding of why it’s important to

Native people to stay together to stay connected to their land that they have been on for

thousands of years. It’s been hard for people in the mainstream to understand

"Why do these people want to stay together?" Why do they want to live in often

remote areas…in what looks like just poverty kinds of conditions. There’s no

understanding of the strong family ties, the extended family, the sense of community that

tribal-ness. So I think the philosophy behind the assimilation kinds of policies were that

in order to be successful in the mainstream context of success, that people would stand a

better chance if they just assimilated into white society and lost that

Indian-ness and

became just like everybody else. After a while it is that sense of Indian-ness and that

sense of community, and extended family and ….. the whole tribe or the nation that is

important to Indian People, and white people have resisted that.

Q: What are the differences between child off reservation and child on reservation.

A child adopted on the reservation or within their tribal group will grow up with the

culture, with the traditions, with the traditional spirituality, with a sense of

themselves as part of that nation…that community. Although they may not be with both

parents, they would have a solid sense of themselves as they grew up. As not only as a

native person, and knowing what that meant to them, but also as a member of the community,

as a relative to everyone within that nation. A child that is adopted off the reservation

by a non-Indian family would grow up with all the values and traditions of what that

family may be. I think the biggest difference between those two situations would be that

our United States nation value system is based on the individualistic kind of society while

native nations are based on collectivistic kinds of societies and the whole values and

reason for being there is to be a good relative and to help the people. Whereas in

mainstream society the value is more on becoming successful, on becoming all you can be,

getting all that you can get and it’s more what an individual can achieve instead of

…..helping the people.

Q: How about the History of Boarding schools

It was early in the 1900’s that children began to be sent away to boarding schools

when they were 4, 5 or 6 years old and the idea again, was to…it began because many

of the treaties specified that the United States government would be responsible for the

education of the children. So again the idea was that the children would do much better if

they learned how to function in mainstream society. It was difficult teaching them to do

that. when they went home at night to a very different kind of society were more

influenced by the values of their parents and the community. So taking them away from

those influences and leaving them in boarding schools where essentially 24 hours a day,

the (mainstream values and ways of doing things could be taught to the children. Some of

those boarding schools were government run boarding schools, and (then ) became affiliated

with various churches in this area…mostly the catholic church. The ideas again, was

to kind of educate the Indian-ness out of that child. and it was done with good intentions

and the belief that these children were going to be better off. In some way by being able

to blend in and becoming a member of mainstream society. Nobody ever understood how

important it was to people to be a member of their own society and to maintain those

values and traditions and how much that history and culture, and spirituality, how that is

a part of who that person is. I think that people were surprised over the years, very

surprised that people hung on so strongly to that and wanted to return to that. It caused

a lot of trauma for children, if you can imagine being five years old and taken away from

everyone and everything you know, often not understanding English suddenly having to

live for months at a time away from you family and everything you know.

Sometimes children didn’t see their families again until they were grown. Then

suddenly they were back, they were out of the school, they had been educated and had grown

to learn the values of mainstream society, and when they went back to their families, they

no longer fit in their communities, so they didn’t know how to be a relative, you

know, what’s valued so much, in native society, and yet they couldn’t really be

non-Indian either because they looked Indian, so white society wouldn’t let them be

just part of the mainstream. A lot of times people got lost in the middle. And that’s

oftentimes what happened to children who have been adopted by non-Indian families.

Q: How does the trauma manifest itself?

It often becomes most apparent during the adolescent years, um during adolescence is a

time of trying to establish a sense of identity, who am I and how do I fit in? And um

adolescents of all cultures struggle with those sorts of questions. Within each culture

our culture tells us how we decide who we are and how we fit in. Within a particular

culture, any culture, there’s expectations and roles and different ways that we

transmit to a young person how they develop that sense of identity. A native person who

has grown up in a non-Indian home has learned basically how to part of that mainstream,

they’re also at this point in time noticing that they’re different. They notice

that they look different, people see them different. They have to face things like racism

and discrimination. And their white family doesn’t have any understanding of how to

teach them how to cope with those kinds of situations. Oftentimes it’s too painful

for families, they don’t want to think of their child, who, in most cases they love

and care for being hurt by racism because they see them as just one of the family and so

they can’t teach them how to cope with things like that. Oftentimes, when people

adopt, it’s because they’re not able to have children of their own so being

reminded of that adoption is a painful reminder of that inability to have children and

that painful time they went through before they were able to adopt. So in some cases,

children are unable to talk, young people are unable to talk about that adoption and where

they come from and who they really are and incorporate that into the identity they

they’re forming. That may be too threatening to the family. So they have to develop

an identity that doesn’t truly feel like who they are. It feels like something is

missing, it feels like a piece of themselves is still unknown. That’s true across

adoptee generally, you often hear people talk about a sense of just not knowing who they

are because because they don’t know who their biological parents are, where they came

from, what their background is, what happened, why was I given up…those kind of

questions. Cause people to really have a sense of not having a complete identity and

it’s even harder when it’s across racial lines. Because through our culture, we

teach a child how to be a member of that society and so they’re not getting help in

doing that. So you often find young people have a difficult time more so during

adolescence. All the typical turmoil during adolescence is part of that attempt of forming

that identity they act one way with their friends, and another way with their parents and

another way at school and um, they really are trying out different identities, they really

don’t have a solid sense of who they are all the time in any situation, and so a

child, an Indian person who’s been growing up in a non-Indian world, they have an

extra piece that they’re really struggling with trying to understand what that means.

To know (where did they come from?) and often times feelings way deep inside of connection

to something that they don’t know anything about because they haven’t learned

that.

Q: How does the typical person handle the situation?

Well, I guess, you know, a lot of times young people will do things that um are

considered dangerous um maybe even self destructive. If the child has gotten the message

that it’s not OK to be who they really are, that who they need to be is part of the

family they’ve been adopted into, and that they know that deep down they don’t

feel the same, what they can come to do is to hate that part of themselves. That

doesn’t fit in, because any child wants to be loved and accepted and to be part of,

you know to feel part of their family if they don’t feel like all of themselves can

be accepted, or there’s a place that they don’t really even know, or

they’re not sure that that can be accepted, they come to hate that part of themselves

and you can see self destructive kinds of behaviors. There have been some studies that

have shown that these young people are more prone to suicide the kind of behaviors

that

are designed to kill the pain, drug use, alcohol use, running away, acting out kind of

behaviors. Sometimes children are lucky enough, their families really try to help them

learn about who they are too. And that’s an ideal situation. The families open to

letting that child explore, to explore who they are, learn about their background, maybe

even meet members of their family and learn more about the culture, where they come from,

who they are, how they fit in overall. Those young people typically do a lot better. As

you know, adolescence is a time where you swing from one extreme to another, so there may

be times where they um, if they may have the freedom to do that, they may make a real

intense swing of wanting to reject everything they’ve grown up with, and only

identify as the background they’re discovering, but usually they’ll choose to

come back, because how they were raised is part of who they are too. And so they tend to

become more bicultural. But (that’s a much) more positive way for them to adjust.

Q: How does the Indian Child Welfare Act impact this situation?

The Indian child welfare act said that any child who needed to be removed from their

natural home, and placed into foster care or a foster home, would be…the attempt

would be made first to place them in an Indian home. So they would be raised within their

culture, their traditions, their spirituality within the tribe…the tribe would not

lose that member. That ultimately would not have as strong an effect on the future of the

nation. and so, um, but prior to 1978, there were many children who were placed outside of

the tribe. Um Now if a child does have to be placed outside of the tribe or it

has to be

placed in with a non-Indian because there’s no availability or no one, a relative or

somebody that they can place that child with, they know that child is often enrolled in

that tribe, and still a member of that tribe and can later trace back and find who they

are and still be a member of their tribe prior to 1978, that didn’t happen.

Q. Is that pretty much followed today?

Well, no, I think there’s many, many cases where it’s not followed and

it’s particularly difficult where one parent is a member of a tribe and one parent is

non-Indian and most particularly when the non-Indian parent is the mother. Because then if

that child then needs to be placed in foster care or an adoptive home, most often the

child is physically with the mother and the mother makes the decisions and I’ve

worked with a number of cases where that kind of thing has happened and it’s

difficult, where the tribe has to be notified by the court and has to intervene within a

certain amount of time. And say, no, we want this child back.

I know that one tribe that I worked with a couple of years ago had over two hundred

open ICWA cases, ICWA meaning Indian Child Welfare Act that means there had been 200

children who had um, not been placed through ICWA and were paced in non-Indian homes and

the tribe was trying to intervene and have those children placed within the tribe. So

there’s many times when it’s not applied 46:30 the tribes usually have to go to

court.

Q. What’s the answer?

I think that there is still an attitude in many place "Why would anybody want to

be raised on a reservation?" "How can this possibly be good for a child?"

um "What can they possibly gain?" "Wouldn’t it be so much better for

them to be placed in this home in this community" Look what they can be given. And

there’s not as much of an understanding of how difficult and how damaging that can be

to a child's sense of identity. So there is still an attitude of assimilation is best and a

lot of times people don’t understand a lot of times people wonder why do Native

people even want to live together, why don’t they just become like everybody else?

Why don’t they just blend in? Why would they want to live like that? So there’s

not really a lot of understanding about the culture, the values of the culture, the idea

of a collectivistic society within the United States which is known around the world as

being an individualistic society. It’s such a different way of being in the world

that I don’t think there’s a good understanding across those cultures. That this

is right here amongst us here in the United States. I think that people still do believe,

, child welfare workers, judges, social services people, that the child would be better

off if they were raised in a different kind of environment. And of course the stories you

hear about life on the reservation, you hear only the negative things, high poverty, high

unemployment, alcoholism, those kinds of things, you don’t hear about the positive

values, the value of thousands of years of tradition and culture and spirituality that

that child does receive.

Q. Psychological effects of boarding schools…

In many cases, in the boarding schools, there’s a whole range of experiences that

people have had. In the worst cases, there was severe abuse, physical abuse, emotional

abuse and sexual abuse and um I’ve heard about…some of the things you hear

about, you know the trauma of leaving your family, the trauma of not being able to speak

your language any more, and severe punishment for speaking the language, I’ve heard

people talk about…to walk around with a block in their mouth or soap in their mouth

because they were speaking their own language beatings, things like that, most of the boys

had to have their hair cut off , you know, to be more like the mainstream. Um depending on

what the teachings are in that culture about hair, that can be a very traumatic thing,

having your name changed, think of what that does to your sense of identity, all of a

sudden, poof, your name is something else than what you had known it to be. And a foreign

sounding name too because it was to a native language.

There’s a lot of people who reported being sexually abused in the boarding schools

and the bottom line here is you have children who grew up, not in a family, with no models

of what family life is like, no model of what parenting is supposed to do, and so when

they grew up and became parents themselves, they had no idea how to be parents. They had

no role models, they didn’t know what that role was, when you think about it, even

though we say "I’ll never do things the same way my parents did" we tend to

sort of follow the pattern that we know because that’s how we learned that. And so we

have generations of people now who had no model of being in a family and have a very

difficult time and a very mixed up sense of identity. How to fit into the world and where

do they fit there’s also been stories of people who were sterilized while they were

in boarding schools. Again the idea is no more Indian children.

They were the most prevalent during those years, but we still have boarding schools

now. Many people of my generation grew up in boarding schools for at least some of their

years of growing up. Now there’s other people who had very good experiences in a

boarding school, in some cases maybe there was issues in their family where their family

wasn’t able to take care of them so they had a better upbringing by being in boarding

schools. So you’ll find a whole range of experiences, but one of the things that

seems to be real common is a sense of abandonment. Even to a young child, it doesn’t

matter the reasons that mom and dad aren’t there, it’s just that they

aren’t there. It often leaves a very deep sense of abandonment inside that person

which has an impact on their relationships when they’re grown up.

Q. What are the lessons from Lost Bird Story…

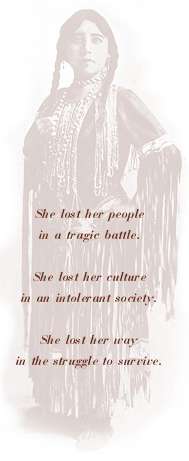

One of the things about Lost Bird is that she was seen as a curiosity, a trophy, I

guess there’s a lot of instances of those kinds of things after every war. I

think there’s a yearning inside for… to be a relative, to be a part of something

greater than what we are individually, to to know your place within the community or the

tribe or the nation or the planet and to know your relatedness to everything else and

that’s not something that…I believe it’s something that is not just

learned...it’s something that’s just got to somewhere there inside of us, hard

wired so to speak it’s there, because I don’t think we could explain things that

happened to lost Bird and how she felt and how she struggled with what she had learned to

become, who she had learned to become she always felt that pull to something else. I think

for a lot of people who have been adopted, and who have experienced those kinds of things,

….It’s easy, even now to just say to say even now, to say well, you take that

child, you put him or her over here and everything will be just fine, hopefully we have a

better understanding that there’s more to it than that. More to who we are and that

goes beyond what this lifetime has been, you know, there’s a spiritual connection to

where we come from.

I think anybody can understand that there will be a short term impact of placing a

child outside of their family, you can imagine the grieving process, even an infant can go

through that, but what we haven’t understood for years is the long term, the lifelong

impact on how people develop and who they develop in to the ways that they cope with their

lives.

|